Scientists from the Faculty of Biology at the University of Warsaw as co-authors of an article in “Nature”

03 04 2025

Dr. Iwona Dembicz, Dr. Łukasz Kozub, and MSc Nadia Skobel from the Department of Ecology and Environmental Protection are co-authors of the article titled “Global dark diversity study reveals hidden impact of human activities on nature”, published in the journal “Nature”. Congratulations!

As part of the DarkDivNet collaboration, research was conducted by over 200 scientists at nearly 5,500 locations across 119 regions worldwide. The project was coordinated by a team from the University of Tartu in Estonia. The collaboration began in 2018, based on an idea by Prof. Meelis Pärtel, the lead author of the study.

At each site, local researchers recorded all plant species and identified the dark diversity – native species that could live there but were absent. This allowed them to understand the full potential of plant diversity at each site and measure how much of the potential diversity was actually present. This way of measuring biodiversity revealed the hidden impact of human activities on natural vegetation.

Researchers from the Faculty of Biology at the University of Warsaw conducted research in north-eastern Poland, southern Ukraine and Switzerland. Participation in the project required them to select study locations (a minimum of 32 study plots of 100 m2 representing local ecosystem diversity) approved by the project coordinators, carry out field surveys according to a defined methodology and process the collected data accordingly.

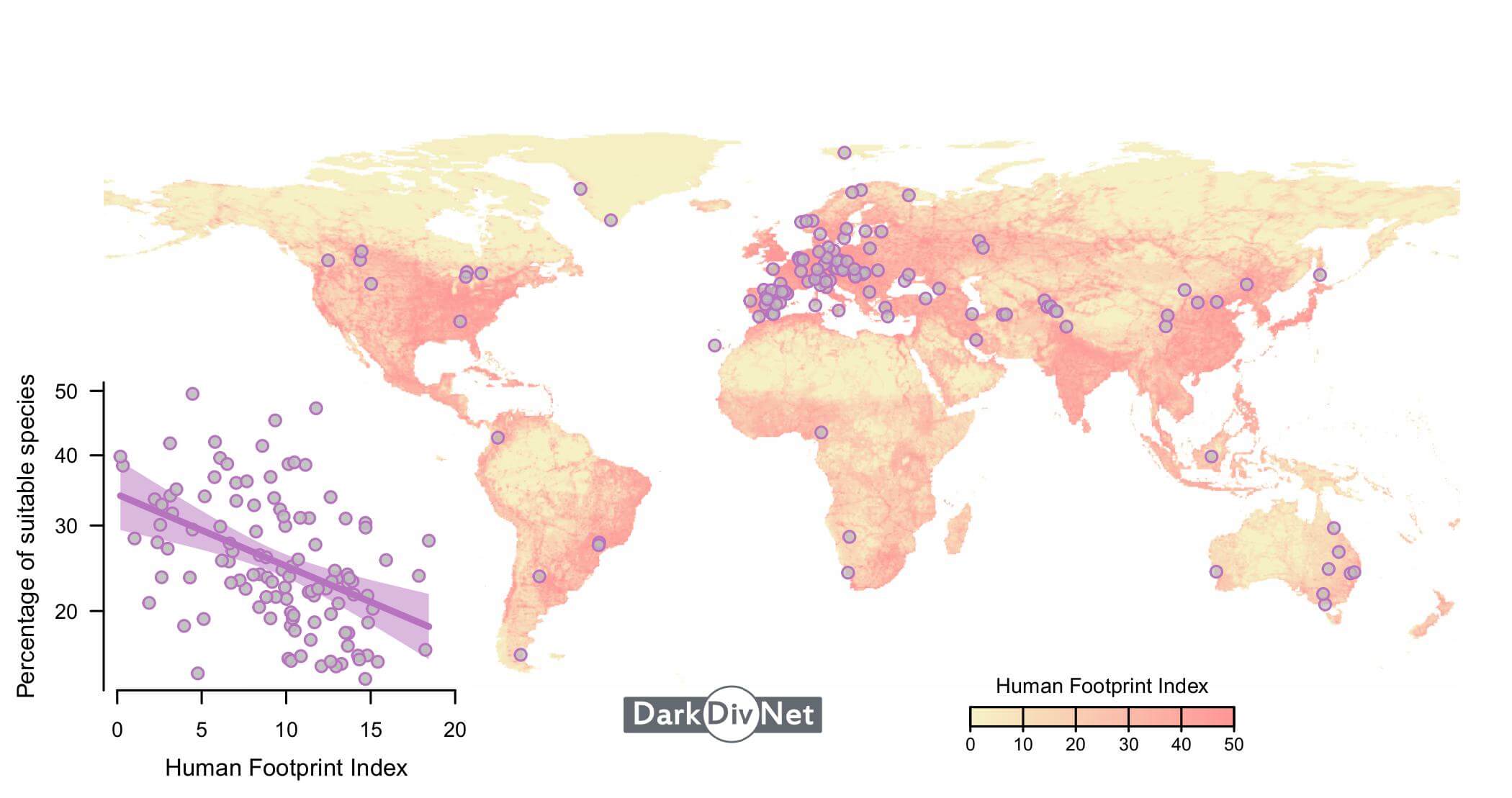

In regions with little human impact, ecosystems typically contain over a third of potentially suitable species, with other species remaining absent mainly due to natural reasons, such as limited dispersal. By contrast, in regions heavily impacted by human activities, ecosystems contain only one out of every five suitable species. Traditional biodiversity measurements, like counting the number of recorded species, did not detect this impact because natural variation in biodiversity across regions and ecosystems hid the true extent of human impact.

The level of human disturbance in each region was measured using the Human Footprint Index, which includes factors like human population density, land-use changes (such as urban development and agriculture), and infrastructure (roads and railways). The study found that plant diversity at a site is negatively influenced by the level of the Human Footprint Index and most of its components in a surrounding area, up to hundreds of kilometres away.

Prof. Pärtel summarises, “This result is alarming because it shows human disturbances have a much wider impact than previously thought, even reaching nature reserves. Pollution, logging, littering, trampling and human-caused fires can exclude plants from their habitats and prevent recolonization. We also found that the negative influence of human activity was less pronounced when at least one-third of the surrounding region remained pristine, supporting the global target to protect 30% of the land.”

The study highlights the importance of maintaining and improving ecosystem “health” beyond nature reserves. The concept of dark diversity provides a practical tool for conservationists to identify absent suitable species and track progress in restoring ecosystems.